Israeli artificial pancreas may one day cure diabetes

Ahead of International Diabetes Day, November 14, Israeli startup Betalin Therapeutics announced that it is beginning the application process for clinical trials of its revolutionary artificial pancreas.

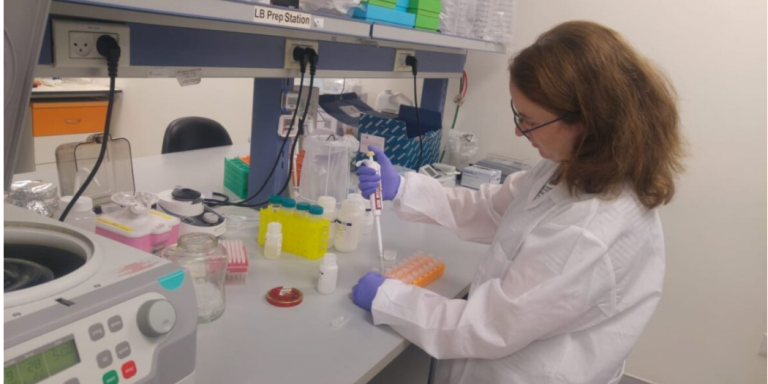

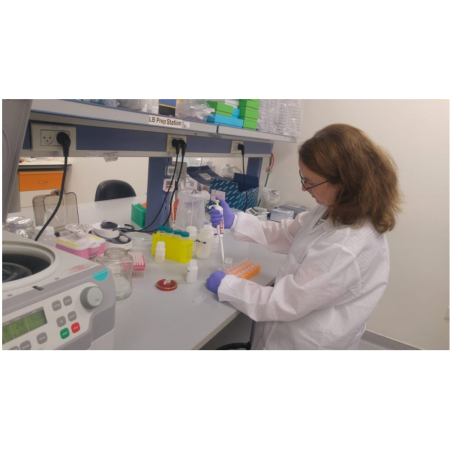

The Engineered Micro Pancreas from Betalin Therapeutics is heading closer to clinical trials in humans.

Betalin’s Engineered Micro Pancreas (EMP) aims to free patients suffering from the most severe types of diabetes from constantly monitoring blood-sugar levels and injecting insulin. About 160 million people are insulin dependent.

The road to an Israeli-made artificial pancreas has been a decade in the making.

When ISRAEL21c first reported on Betalin in 2015, the company had just been founded, based on research in the laboratory of Prof. Eduardo Mitrani at the Hebrew University of Jerusalem. (Mitrani is continuing his academic work while serving on Betalin’s scientific advisory board.)

In Type 1 diabetes, insulin-producing cells (known as “beta cells” – hence the name Betalin) in the pancreas don’t function properly.

Doctors have tried implanting patients with islets of beta cells extracted from the pancreas of a donor. Unfortunately, the implanted cells don’t survive long even with immunosuppressive drugs. Half of all transplanted patients are back on insulin injections one year later and 90% revert to insulin dependency within five years.

The relapse rate is so high because beta cells aren’t naturally designed to survive on their own in the body.

“They need to be surrounded by some sort of supporting tissue – a scaffold, we call it,” Betalin CEO Nikolai Kunicher tells ISRAEL21c. “The scaffold mimics the natural environment the cells are used to inside the body. It helps them function better and live longer.”

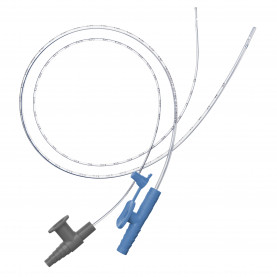

The EMP is Betalin’s scaffold. With a diameter of 7 millimeters and a thickness of 300 microns, the EMP is composed of lung tissue from a pig and insulin-secreting beta cells, either from a donor or created in a lab.

Replacing the pancreas

The EMP does not jump-start a malfunctioning pancreas; it actually replaces it. The artificial pancreas “senses the body’s glucose level and the beta cells secrete the optimal amount of insulin,” says Kunicher, who has a PhD in microbiology.

The EMP is implanted under the skin – usually in the leg – using only local anesthesia and quickly attaches to the vascular system. The process should take less than an hour.

Betalin is expecting a price of $50,000 per implant, although insurance should cover most of that. “The cost of complications around diabetes and the cost of insulin is so high, government and insurance companies will jump on it,” Kunicher predicts.

How high? The global Type 1 diabetes market is expected to be worth $25.52 billion by 2024. The World Health Organization estimates that nearly half a billion people worldwide suffer from Type 1 or Type 2 diabetes – some 8.8% of the adult population. Diabetes doubles the risk of early death.

Creating beta cells

For Betalin Therapeutics, the hard part is acquiring enough beta cells to fill an EMP. The only way to get human beta cells today is from a cadaver. Up to three donors are needed for each patient to supply the 400,000 to 500,000 islets required per infusion.

That’s led to a red-hot medical technology niche for companies creating beta cells in a lab.

In September, for example, Vertex Pharmaceuticals paid $950 million to acquire Boston-based Semma Therapeutics, which derives beta cell islets from human stem cells.

Betalin can use beta cells from third parties like Semma, Kunicher says, but the company is also working on making its own. Betalin was recently awarded a binational collaboration grant by the Israel Innovation Authority and the Italian government to work with beta cell expert and transplant researcher Prof. Lorenzo Piemonti.

Years of clinical trials ahead

Diabetes patients will have to wait a few years before the technology is fully tested. So far, Betalin has conducted only animal trials.

In preclinical studies in a mouse model of diabetes, published in the medical journal PLOS ONE, approximately 70% of the mice in which the EMP was implanted did not need further insulin injections, even for the longest period tested (90 days after implantation).

Kunicher says it will take another year – and an additional $5 million, which the company is in the process of raising – to complete all the regulatory work required to begin testing in humans.

Betalin has set up international testing collaborations with clinics in Germany, England, the United States, Italy and China.

If all goes well, it would then be another five years before the EMP reaches the market.

Betalin’s labs are in the Jerusalem Bio Park on the campus of Hadassah-Hebrew University Medical Center. The staff of eight includes founder Joshua “Shuki” Hershcovich, a serial entrepreneur who previously founded Sonovia (formerly Nanotextile).

Two past winners of the Nobel Prize in chemistry sit on the company’s board of directors: Israel-born University of Southern California Prof. Arieh Warshel (2013) and Yale University Prof. Sidney Altman (1989). Altman has diabetes and his brother died from complications of the disease.

Speaking of prizes, Betalin won the top spot in the pharmaceutical category at the 2017 MIXiii Biomed conference, Israel’s largest life-science industry event.