TAU-Led Team Develops Novel Method For Early Detection Of Parkinson’s

Scientists at Tel Aviv University, working together with colleagues at Cambridge University in the UK and the Max Planck Institute in Gottingen and Ludwig-Maximilians-Universität München in Germany, say they have identified a novel method for detecting the early aggregation of a protein that signals the onset of Parkinson’s disease in mouse models.

The discovery could introduce treatment that has the potential to significantly delay disease progression, the researchers say in a study published earlier this month in Acta Neuropathologica, a monthly peer-reviewed scientific journal.

Parkinson’s disease is a progressive neurodegenerative disorder that affects dopamine-producing neurons in a specific area of the brain called substantia nigra. It has four main symptoms and can be difficult to accurately diagnose in its early stages. Symptoms develop gradually and include shaking or tremors, a slowness of movement called bradykinesia, stiffness in the extremities, and postural instability. Diagnoses are often first made by family physicians after which neurologists are usually consulted, according to the Parkinson’s Foundation.

There is no cure and treatment involves medication for symptoms – though none that can reverse the effects of the disease – and surgical therapy.

In their study, the team of scientists from Israel, the UK, and Germany, developed a new method for tracking the early stages of the aggregation of a protein called alpha-synuclein, “a hallmark of Parkinson’s disease using,” Tel Aviv University said in a statement.

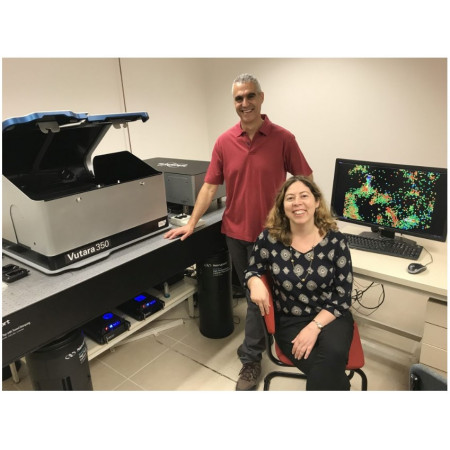

“This is extremely important because we can now detect early stages of alpha-synuclein aggregation and monitor the effects of drugs on this aggregation,” said Dr. Dana Bar-On of Tel Aviv University’s Sagol School of Neuroscience, a co-author of the study, in a university statement.

Professor Uri Ashery, co-author of the study and head of the Sagol School of Neuroscience and TAU’s George S. Wise Faculty of Life Sciences, said the discovery was “a significant step forward in the world of Parkinson’s research.”

In their study, the researchers working with their UK counterparts say they were able to detect different stages of the aggregation of this protein and correlated the aggregation with the deteriorating loss of neuronal activity and deficits in the behavior of the mice, Prof. Ashery said.

In collaboration with their German colleagues, they were then able to illustrate the effect of a specific drug, anle138b, on this protein aggregation and correlated these results with the normalization of the Parkinson’s phenotype in the mice.

“By detecting aggregates using minimally invasive methods in relatives of Parkinson’s disease patients, we can provide early detection and intervention and the opportunity to track and treat the disease before symptoms are even detected,” Prof. Ashery said in the university statement.

Dr. Bar-On explained that the next step is to implement the methods in a minimally invasive manner with Parkinson’s patients for the use in the early diagnosis, after which the scientists hope to expand their research to family members of affected patients.

Parkinson’s disease will affect approximately one million people in the United States by 2020, while ten million worldwide are currently living with the disease. Some 60,000 Americans are diagnosed with Parkinson’s disease every year.